The price of being "avant-garde"

Mid-May--the tourist season is in full force here in Paris. Yesterday, at the Louvre, there was a line of people outside the main entrance (the main "great" glass pyramid) that snaked all the way down the plaza, for at least half a kilometer . . . to the Cour Carrée. Of course, inside, it was quite a circus as well. People strolling by Carpaccio's Saint Steven in haste to "get there" (in front of the bulletproof shrine).

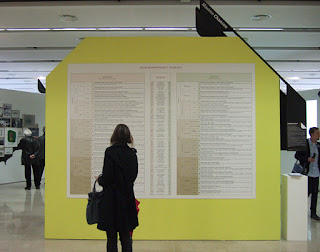

My friend Arielle and I had gone to a contemporary art "salon" just outside the city the day prior, a yearly juried show called the "Salon de Montrouge". The winner of the "Grand Prix" this year was Maxime Chanson, someone who until now appears to have been a "figurative" artist (as per his personal website). For his winning piece at the salon, he created a large spreadsheet, which aimed to catalog and define the different trends in contemporary art:

It is a thought provoking piece. It is an inventory of his reflections on what is the art scene from his point of view and implicates his immersion in the historicity of finding a place in contemporary art. He divides the enterprise of being a contemporary artist into two main categories, the "motor" of art production and the "means" of this production. Each has subcategories--for "motor" this would be "to understand", "to make", "to feel"; for "means, there are "Installations (ensemble)", "Objects", and "Images". Each of these are broken down into even smaller subcategories etc. etc. Just as an example, the German painter Neo Rausch was cited as a contemporary artist who would exemplify someone who is interested in making oneiric theatrical work by means of an image that is immobile, handmade--a painting. I wonder though, could Rausch not be someone who wishes to understand societal codes of unjust exclusion by denouncing the irrationality behind these à prioris through derision? I forget exactly how the New York based impresario of relational aesthetics Rirkrit Tiravanija was defined but I can see him as an artist who searched to understand the perception and limits of space by means of creating an installation based on the context of the work with the visitor as a sort of playful interaction. But to think of it, Tiravanija could also be an artist that studies societal codes of conditioning mimicry or even someone who wishes to express the sensuality of our bodies' fragility in a mise en scène (on a visit earlier this year, the odors of his curry inundating the contemporary floors of the MoMA gave me just a bit of nausea).

My point is that any endeavor of macro-aesthetics is fraught with arbitrary inclusions and exclusions in the very porous walls of contemporary art. Art objects can easily span many of Chanson's definitions. His is insistent, however, and insists that clarity and explanations are the last taboos in contemporary art.

My point is that any endeavor of macro-aesthetics is fraught with arbitrary inclusions and exclusions in the very porous walls of contemporary art. Art objects can easily span many of Chanson's definitions. His is insistent, however, and insists that clarity and explanations are the last taboos in contemporary art.

I started thinking, in the studio yesterday, what it took for someone like him, a self-proclaimed figurative artist, to end up spending all his time in making rather arbitrary definitions to "explain and clarify" art.

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, there is a large collection of work by Marcel Duchamp, from his very early paintings (traditional landscapes, genre scenes), which are so-so, neither good nor very bad nor "radical", to his last work, the iconic and rather self-fulfilling prophecy of an installation called "Etant Donné", which involves a peep-hole, a nude woman in a landscape holding an oil lamp with a kitschy waterfall "in the distance". Self-fulfilling because in the saga of reification and historicism that is quintessential to our "avant-garde" contemporary art world, the mandala of holiness that emanates from Duchamp' and his also prophetic last piece has become the quintessential tautological raison d'être (the logic being "I will make Duchampian work because Duchamp is God and so I am also holy).

Duchamp was not really all that interested in painting. As a painter, his most successful piece, the famous "Nude descending a staircase" is a brown-ochre painting of the amalgam of his ideas of the "avant-garde" of his time--Cubism and Futurism by way of the photography of Edward Muybridge--painted in 1912, at least 5 years after the revolution that was Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon (not that it matters, but just to point out its retardataire position in the timeline of 20th century avant-gardism). Of course, he is famous for placing industrial objects in exhibitions--urinals, hat-hangers, and also known to be an excellent chess player. I am linking below an old Robert Hughes video on Duchamp, it is excellent as so much is said while being unpronounced:

Duchamp was not really all that interested in painting. As a painter, his most successful piece, the famous "Nude descending a staircase" is a brown-ochre painting of the amalgam of his ideas of the "avant-garde" of his time--Cubism and Futurism by way of the photography of Edward Muybridge--painted in 1912, at least 5 years after the revolution that was Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon (not that it matters, but just to point out its retardataire position in the timeline of 20th century avant-gardism). Of course, he is famous for placing industrial objects in exhibitions--urinals, hat-hangers, and also known to be an excellent chess player. I am linking below an old Robert Hughes video on Duchamp, it is excellent as so much is said while being unpronounced:

One starts to wonder, if Duchamp was not just too limited in ability to be able to continue to be a painter, either way, he definitely had little love for it. And to say that the background of a painting has no meaningful function is really just bar none quite, well, imbécile.

Comments

Post a Comment