The end of day-light saving time in Paris is today

I recently got a dog, well, recent is relative; the little puppy that I brought home is now nearly at her adult size and all in a blur and a flash. I have noticed recently that she no longer responds simply to praise and treats. Sometimes, it seems to me, she tests limits and looks for correction. I wonder if this principle of "push and pull" if you will does not apply to most things in life.

We were having dinner at the home of friends who had recently moved back to Paris after years abroad as expatriates--a very cultivated couple who work in the arts, as a specialist in the restoration of antiquities, and a professor of literature. The conversation we had was varied but I was asked about my artistic roots at one point. Strangely, I had been thinking about this for the past few months. What are the artistic roots of a painter who was educated in the United States of America?

No doubt, many great educators come to mind, those Europeans who arrived and trained a generation of painters who eventually passed down what they learned to the little ones that came afterward. I am thinking of Hans Hoffman, who seemed to have influenced so many of the painters from New York that had crossed my path. I also had the luck to have known a painter who had studied with Max Beckman in Saint Louis and another who was very enthusiastic of the teachings of Josef Albers. Those would be the roots I guess that chance and hazard had chosen for me. I had no early exposure to the beaux-arts tradition as it may still exist in the New World, nor the school of American realism that may still exist in the off-spring of Thomas Eakins.

Relaying this information to my hosts, it was quite surprising for me to learn that they had absolutely no idea who Hans Hoffman was. For an American who grew up many years after the glory of the triumph of the New York School of painting, it would seem that everyone would know who Hans Hoffman was -- the grand master professor of American Action Painting, his "push and pull" were like incantations and chants that was repeated constantly in art school. But not so. In fact, now that I think of it, I am not sure that the Centre Pompidou has much of his work in their collection. I have not seen any of his work exhibited there.

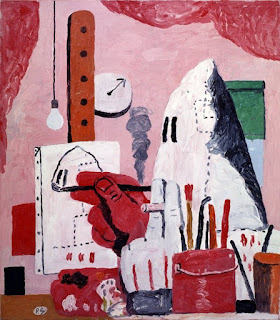

I have been living in Paris since November 2009. That makes it literally six years in a week. I am less and less surprised by things that occur here and the naiveté and wonder of being here (oh, I miss that sense of constant wonder and wonderment) has changed into something approaching a mixture of admiration and fatigue--admiration of the endless and astounding beauty of this city and fatigue of the harsh realities of living in Metropolis. I still continue to find a certain difference of the à prioris that separates an American from a Parisian. For us, the triumph of the New York School is completely evident and historical fact. We place without any bad faith the whole first two generations of AbEx painters in their own glorious pantheon. We sometimes expect others--Europeans, Parisians, even the most cultivated of artists, to have the same à prioris as us. But that isn't the case. Philip Guston, who is a deep and constant reference point for me, if he is known at all, is known as a minor second generation (thus "decadent" by definition) footnote to many here. And in certain circles, yes, they exist, the so called triumph of the New York School is seen as just polemics forwarded by the CIA during the Cold War and nothing more.

The joke is that America is "barbarie" and its people rough and uncultivated. It is all said with a lot of jest and humor, but often, it is said pointedly. I sometimes feel like Guston's poor hooded klansman painting forlornly in front of his easel. The gusto of Guston's figuration, its brutish power, its dark narrative wit and humor stay within me as deep ideals. And a stone's throw away from the studio where I work is the home of some of the greatest paintings of the Old World-- the finesse and virtuosity of Van Dyck, the compositional power of Poussin, the mystical sublimity of Rembrandt. One does not necessarily have to see dichotomy in any of this for certainly the continuity is evident, but it is certainly true also that one's own cultural references do not necessarily pass through to those from another continent.

We were having dinner at the home of friends who had recently moved back to Paris after years abroad as expatriates--a very cultivated couple who work in the arts, as a specialist in the restoration of antiquities, and a professor of literature. The conversation we had was varied but I was asked about my artistic roots at one point. Strangely, I had been thinking about this for the past few months. What are the artistic roots of a painter who was educated in the United States of America?

No doubt, many great educators come to mind, those Europeans who arrived and trained a generation of painters who eventually passed down what they learned to the little ones that came afterward. I am thinking of Hans Hoffman, who seemed to have influenced so many of the painters from New York that had crossed my path. I also had the luck to have known a painter who had studied with Max Beckman in Saint Louis and another who was very enthusiastic of the teachings of Josef Albers. Those would be the roots I guess that chance and hazard had chosen for me. I had no early exposure to the beaux-arts tradition as it may still exist in the New World, nor the school of American realism that may still exist in the off-spring of Thomas Eakins.

Relaying this information to my hosts, it was quite surprising for me to learn that they had absolutely no idea who Hans Hoffman was. For an American who grew up many years after the glory of the triumph of the New York School of painting, it would seem that everyone would know who Hans Hoffman was -- the grand master professor of American Action Painting, his "push and pull" were like incantations and chants that was repeated constantly in art school. But not so. In fact, now that I think of it, I am not sure that the Centre Pompidou has much of his work in their collection. I have not seen any of his work exhibited there.

I have been living in Paris since November 2009. That makes it literally six years in a week. I am less and less surprised by things that occur here and the naiveté and wonder of being here (oh, I miss that sense of constant wonder and wonderment) has changed into something approaching a mixture of admiration and fatigue--admiration of the endless and astounding beauty of this city and fatigue of the harsh realities of living in Metropolis. I still continue to find a certain difference of the à prioris that separates an American from a Parisian. For us, the triumph of the New York School is completely evident and historical fact. We place without any bad faith the whole first two generations of AbEx painters in their own glorious pantheon. We sometimes expect others--Europeans, Parisians, even the most cultivated of artists, to have the same à prioris as us. But that isn't the case. Philip Guston, who is a deep and constant reference point for me, if he is known at all, is known as a minor second generation (thus "decadent" by definition) footnote to many here. And in certain circles, yes, they exist, the so called triumph of the New York School is seen as just polemics forwarded by the CIA during the Cold War and nothing more.

Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969

The joke is that America is "barbarie" and its people rough and uncultivated. It is all said with a lot of jest and humor, but often, it is said pointedly. I sometimes feel like Guston's poor hooded klansman painting forlornly in front of his easel. The gusto of Guston's figuration, its brutish power, its dark narrative wit and humor stay within me as deep ideals. And a stone's throw away from the studio where I work is the home of some of the greatest paintings of the Old World-- the finesse and virtuosity of Van Dyck, the compositional power of Poussin, the mystical sublimity of Rembrandt. One does not necessarily have to see dichotomy in any of this for certainly the continuity is evident, but it is certainly true also that one's own cultural references do not necessarily pass through to those from another continent.

Roy Forget, Le Saint Germain, Mazrâ, 2014-2015

Comments

Post a Comment